Dinner with Barack Obama, mansions on both US coasts and dazzling modern art collections — from Frank Stella to Jean-Michel Basquiat. These are all solid bragging points when you’re sitting at finance’s top table.

And yet for the three core founders of HPS Investment Partners, how they spend their fortune is much less striking than how they made it. In 2016 the private credit firm bought itself out of JPMorgan Chase & Co. in a complicated deal valuing it at close to $1 billion. As it wrestles today with the idea of a public listing, it could be worth roughly eight times as much.

Perhaps more than anyone else, the usually secretive HPS has come to personify the remarkable rise of private credit as a usurper of traditional Wall Street lending. And the founding trio has the billions to prove it.

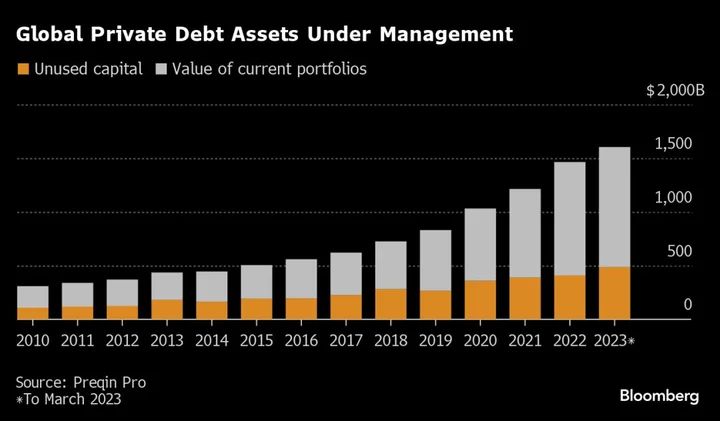

For more than a decade Scott Kapnick, Scot French and Mike Patterson have been at the vanguard of turning a niche area of finance — where “nonbank” funds lend money to riskier companies — into a $1.6 trillion juggernaut.

That all three worked before at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., another grand name of investment banking, adds a layer of spice to their story. HPS, like its fellow direct lenders, is now busy cutting off former Wall Street comrades from one of their favorite historic money spinners: corporate loans.

A 64-year-old Midwesterner, Kapnick is usually understated. But he doesn’t hold back when predicting private capital’s overthrow of the financial order. “You’re seeing the rebuilding of Western capital markets beyond the banking system,” the HPS chief executive officer tells Bloomberg in a rare interview.

Whether that’s a good thing depends on who you ask. Private credit’s fans say stripping risky loans from the balance sheets of systemically important banks and shifting them to specialist lenders will strengthen the finance system.

But some, such as the International Monetary Fund and the Bank of England, question whether a “shadow banking” network out of the public market’s gaze creates its own dangers of weak transparency and illiquidity. Colm Kelleher, UBS Group AG’s chairman, warned this week of a private credit “asset bubble.”

Despite its meteoric rise, outsiders know little about how HPS operates and how it quietly amassed $100 billion of investor assets. This story, the first account of its climb to its lofty peak, is based on interviews with more than a dozen people, including former and current employees and senior rivals. Many asked to remain anonymous discussing the intensely private firm and only a few agreed to talk about its ownership structure and financial information.

Goldman Genesis

Ironically, it was the zeal of post-financial crisis regulators that created the conditions for the evolution of firms like HPS. Frustrated by the crackdown on “casino” banking after Lehman Brothers’ collapse, many of the finance world’s animal spirits were left scrambling to find a place that still hungered for big, buccaneering bets. In short, the Wall Street of old.

In recent years banks have tended “to gravitate toward businesses where they’re getting fees and not taking investment risks,” says Patterson, 48, an ex-Navy officer who graduated from Harvard and Stanford. “Maybe that’s not Wall Street 30 years ago, but it’s the Wall Street of today.”

As banks have retreated from risky lending, direct lenders have marched in. HPS and its ilk make loans with cash they’ve raised from professional investors such as insurers, pensions and wealthy individuals, unlike banks which use ordinary customer deposits. That difference has kept the industry out of the crosshairs of regulators — until now, at least — allowing it to boom unhindered.

Kapnick and his cohort got in early. It was in 2007, a year before Lehman’s implosion, that HPS’ founders grabbed the chance to go their own way.

The HPS boss had been cohead of global investment banking at Goldman Sachs, where he’d witnessed firsthand the genesis of one of private credit’s earliest iterations: mezzanine finance. This type of loan sits between equity and more senior forms of debt in a company’s capital structure, putting the lender toward the back of the queue on getting their money back if a borrower goes bust. Returns are better than bog-standard debt. The risks are greater.

One feature of the Goldman Sachs mezzanine franchise was that it raised money from outside investors to fund the loans, a blueprint for how private credit firms work today. The business was created by Muneer Satter, a Chicago native like Kapnick who remains close to the HPS boss.

Kapnick, a Goldman Sachs partner since 1994, noticed that the bank’s nearest rival JPMorgan didn’t have a competing mezzanine business. So in 2007 he jumped ship to build one as a unit of Highbridge Capital Management, an investment firm that sits within JPMorgan Asset Management. Others, including the now governing partners French, Patterson, Purnima Puri and Faith Rosenfeld, joined him. HPS was born.

“I had experience with Goldman and how they were originating and investing within the bank,” says Kapnick. “There was space under JPMorgan where they could grow a similar franchise.”

The University of Chicago alum had built before. A polished figure with a fondness for big-picture thinking, he cut his teeth creating the Goldman Sachs franchise in Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He’s from finance stock, too. His father Harvey Kapnick led Arthur Andersen in the 1970s, leaving after he raised concerns about the closeness of its accounting and consultancy arms, a central aspect of the subsequent Enron scandal and Andersen’s demise.

In the beginning, being perched within Highbridge and JPMorgan suited Kapnick and his team, giving them a leg-up over rivals. HPS (the acronym stands for Highbridge Principal Strategies) had access to a crew of JPMorgan salespeople to pitch clients, and to the Wall Street titan’s capital.

While the tie-up went well at first, the Lehman aftershocks kept rippling into the next decade, and regulators kept turning the screws on banks. “JPMorgan was going to provide us with capital and the possibility of deal flow, including allowing me to fund a young, talented team,” Kapnick recalls. “All these conditions were matched, but then the crisis happened and several of those conditions changed. It was difficult to see us grow as significantly.”

In 2016 Kapnick and the rest of the senior team decided to part ways with the bank. A deal was done using about $300 million of debt financing from Bank of America Corp. and JPMorgan and about $100 million of the partners’ cash.

JPMorgan kept an HPS stake and agreed to an earnout structure based on performance. It exited in two stages as HPS got new equity from Dyal Capital in 2018 and Guardian Life in 2022. All told, the bank made between $750 million and $1 billion through its sale of HPS including profits earned along the way.

To this day the founder trio remains in charge, having lifted assets from $34 billion in 2016 to above $100 billion. Together, they own about two-thirds of HPS. Based on the mooted value, they’re all billionaires.

HPS declined to comment on its ownership structure or valuation. JPMorgan didn’t respond to requests for comment on its exit terms.

Old Friends

For an idea of how HPS operates, one particular deal this year stands out. The purchase of an Austrian packaging maker doesn’t sound especially glamorous, but it’s the kind of lucrative transaction that used to be meat and drink to Wall Street bankers, who’d typically pull together the debt financing used by private equity firms when snapping up bigger companies.

The buyout of Constantia Flexibles by One Rock Capital Partners is doubly noteworthy because it was a team from HPS’ old parent, JPMorgan, that was working with other banks on a €1.4 billion ($1.5 billion) loan package to help finance the deal. Unbeknown to the banks, top HPS dealmaker Vikas Keswani was working with One Rock on an alternative, according to people with knowledge of the deal.

Keswani offered One Rock €1.5 billion if it sidestepped the banks and went with HPS alone, the people familiar say. It accepted. As well as the extra cash, One Rock got more certainty over what it would pay, removing the risk that a deterioration in credit markets, where the banks would have offloaded the debt to a syndicate of investors, would increase the financing cost. It also had an option to defer some interest payments.

JPMorgan, One Rock and HPS declined to comment on the Constantia episode.

HPS’ personal contacts are often central to its modus operandi. The One Rock relationship, for example, goes way back. French and the buyout firm’s cofounder Tony Lee began their careers at Salomon Brothers together.

Its willingness to fly solo, and bid high, is also pivotal. That in turn points to a key risk in private credit: If a borrower goes bust, the hit isn’t shared by a broad syndicate. While direct lenders charge a premium and their loans are pegged to base rates, a borrower may struggle to maintain spiraling interest payments. The nascent industry is untested in a serious recession.

“This is a market that’s so private and has gotten so large, and its fundamental strategy is to use leverage,” says Christina Padgett, head of leveraged finance research for Moody’s Investors Service. Piling debt onto an acquired company “has been fine for the last 15 years since rates were low,” she adds, “but as that’s changed those businesses are now increasingly fragile.”

“We expect to see growing stress in the private segment of the loan market,” fund giant Pimco wrote in a note this week.

Calculated Gambles

The HPS founders say they’re happy to back their own number crunching when making chunky wagers, arguing that it’s what sets them apart.

“We don't just buy the market,” Patterson says. “So much of the credit and equity business is along the lines of ‘show me what other people have done and we’ll do something like that.’ That’s a totally fine way to deliver ‘down the fairway’ results but it becomes dangerous as what everyone actually does is things that are just a little bit worse than the last person.”

Speaking about hefty loans — to businesses such as Constantia, aircraft maker Bombardier Inc. and Ambassador Theatre Group — he adds that HPS doesn’t only check out what comparable companies are worth: “We're looking at detailed historical financials, a deep analysis of the company and taking some additional downside protection” on how a loan’s structured.

“Our competitors refer to us as the nerds of private credit and we take no offense,” says French, who along with Patterson manages four-fifths of HPS’ assets. Patterson looks after the senior loans, which pay out first if a company hits trouble. French takes care of the off-piste, higher-yielding gambits; deals that other debt funds might not have the stomach for.

Patterson, who owns an organic farm in Connecticut with his wife Nina, likes to be patient and tends to fret about worst-case scenarios. French, a bicoastal jetsetter with a passion for sporting events, is less restrained. His funds offer anything from junior debt to equity, stretching the returns it can generate — and the very definition of private credit.

One of French’s jewels is Authentic Brands, owner of Reebok, Juicy Couture and Brooks Brothers. He was introduced to its CEO, Jamie Salter, by another entrepreneur whom he’d lent to. In 2021 HPS made an equity investment alongside CVC Capital Partners that valued Authentic at nearly $13 billion. A new investment by General Atlantic has lifted that to $20 billion.

The Midas touch hasn’t always been apparent, though. HPS was forced to take control of Brazilian call-center operator Atento after its value plunged. It’s in discussions to take over another struggling borrower, Berlin Brands, an e-commerce company backed by Bain Capital.

Some attempts to diversify HPS have foundered, too, including a growth-equity business. Its targeting of “NAV lending” — providing debt to buyout firms secured on their holdings — and real-estate loans is faring better, bolstered by a fresh batch of Goldman Sachs recruits.

Mike Koester, cofounder of 5C Investment Partners and former cohead of alternative investments at Goldman Sachs, who’s worked with Kapnick and Patterson, says they’ve brought the “Goldman ethos” to HPS: “Only a few firms can do both deep investment work and develop deep relationships. HPS is one of the few, and has the capability to do it at scale.”

Private Pleasures

For a firm as active as HPS, it’s surprising how few people outside private capital even know about it. Listed rivals such as Blackstone Inc. and Apollo Global Management Inc. built their names over decades in private equity.

Two direct peers, Ares Management Corp. and Blue Owl Capital Inc., have done initial public offerings. HPS has been thinking about following suit at a valuation of about $8 billion and has been working with JPMorgan on this and other long-term strategic plans. The bank declined to comment.

“The path that others have taken going public made sense for them and seems to have worked well for those firms,” says Kapnick. “But my job as CEO is to make sure we don’t have to do anything.”

One advantage of a listing is that HPS could use its shares for acquisitions. Many smaller rivals are struggling to raise funds and want to sell up instead.

Staying private has other complications. After the partners bought HPS, several senior employees quit, complaining about not getting adequate equity stakes, according to people familiar. HPS does now award equity to its top performers through a discreet partnership scheme, the same people say, although there are no public references to that.

Ownership has made the core founders very rich. Kapnick has a 12,000-square foot Florida mansion worth about $50 million and last year sold a limestone house in New York’s Upper East Side for $27.5 million. The trio are all collectors of art, including works by Julie Mehretu and Damien Hirst, as well as Stella and Basquiat.

The firm is also a presence on the billionaire philanthropy scene. Kapnick has a $55 million personal foundation. Recently the HPS founders hosted a client event, and a dinner for friends, with ex-President Obama after agreeing to donate $10 million to a new athletic center in Chicago.

Conversations with current policymakers may be less convivial. US officials, the European Union, the IMF and the BoE have all voiced fears about the opacity of nonbank finance titans. While private capital’s rise does move credit risk away from banks, the asset class is illiquid by nature. Investors such as insurers and pension funds will find it hard to sell their positions, even if they sour.

Kapnick, however, argues that the industry he helped birth is a bulwark against future crises. “I’m sure there will be moments when you need bad actors looking into,” he concludes. “But regulators will look back and say we have a better, safer banking system.”

--With assistance from Gillian Tan, Laura Benitez, Tom Maloney, Libby Cherry and Claire Ruckin.