Droughts and forest fires are among threats that may scupper Australia’s ambitions to bolster its farming industry into a A$100 billion ($64 billion) powerhouse by the end of the decade.

The country just recorded its driest-ever September, which is jeopardizing the wheat harvest and forcing farmers to sell cattle. This summer’s bushfire season promises to be worse than usual due to the El Niño weather pattern, while new pests, like the bee-killing varroa mite, are yet another hurdle.

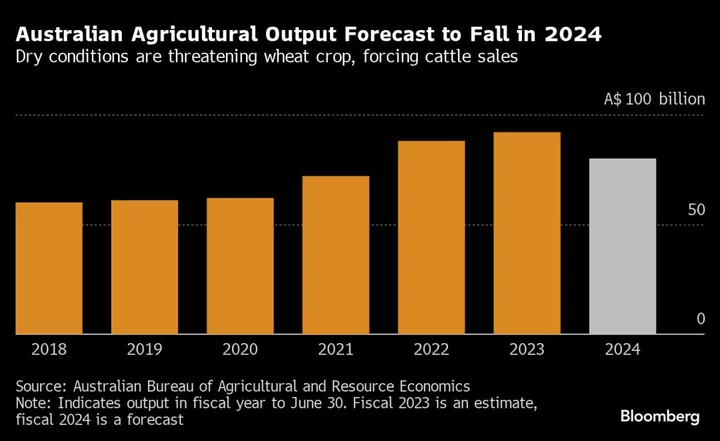

The government is forecasting the production value of Australian agriculture will drop 14% to A$80 billion in the year through June 2024 due to the drier weather and falling commodity prices. In the longer term, climate change is adding to the challenges. Average rainfall has declined at least 15% over the last half-century, while the bushfire season has become longer and more extreme.

While the A$100 billion goal — first announced in 2018 — might be possible by 2030, it would take a lot of factors like weather and commodity prices to line up, said Michael Whitehead, executive director of agricultural insights at ANZ Group Holdings Ltd.

“When we got close to a A$100 billion last year, it was due to a perfect storm of circumstances,” he said. There’s a “strong possibility” that won’t happen again for years, if not decades, he said.

The A$92 billion generated from agriculture in the year through June 2023 was a record, helped by the war in Ukraine boosting wheat prices. Cattle prices were also historically high as farmers restocked their herds following a drought. Australia is one of the world’s biggest meat and grain exporters.

Policy to Blame

Still, Australian farmers say it’s government policy that’s threatening the future of agriculture. “Right now, we’re facing an avalanche of bad ideas, that if seen through will see farmers walk off the land, and indeed see entire industries closed for no good reason,” National Farmers’ Federation President David Jochinke said at a conference in Canberra on Thursday.

Farmers are calling for the abandonment of plans to ban live sheep exports to the Middle East and the establishment of a dedicated visa pathway for agricultural workers. Other contentious issues include water buybacks in the Murray Darling Basin and environmental protection laws.

Agriculture Minister Murray Watt sought to defend government policies in a speech to the same conference, saying he was surprised by the federation’s position and that the government had taken actions to help farmers and improve access to foreign markets.

Read more: Extreme Weather Turns Up the Heat on Investing in Agriculture

Climate Change

While climate change is threatening Australia’s agricultural revenue, the nation is still one of the biggest coal and natural gas exporters. The election of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s Labor government last year had raised optimism its reliance on fossil fuels would be lessened, but that’s been dimmed by approvals to four coal projects since it took office.

Some farmers are more concerned with staying afloat than with the government’s lofty production goals. Justin Everitt, who grows wheat, canola, barley and lupins in northern New South Wales, said he was likely to produce 20% less grain this year after his crops had started to rapidly dry since August.

“It’s nice to aim for big targets, but we need to make sure our farms are profitable first,” he said.

--With assistance from Ben Westcott.

(Updates to add farmer and minister comments in graphs seven to nine)